The Judas within each of us

A contemplative christian engagement with the story of Judas in Holy Week.

In the shadows of Holy Week, just before the horror and beauty of the Triduum, the Gospel reading for Holy Wednesday confronts us with one of the most haunting moments in the Jesus story: Judas Iscariot slipping into the night.

John 13:21–32 tells it simply but devastatingly. Jesus, troubled in spirit, declares, “Very truly, I tell you, one of you will betray me.” The disciples are confused, disoriented. Judas is identified in an almost mystical act—Jesus dipping the bread and giving it to him—and we are told, “After he received the piece of bread, Satan entered into him.” Judas leaves, and the Gospel says, chillingly, “And it was night.”

It’s tempting to paint Judas in simple terms—as the villain, the traitor, the black sheep who brings about Jesus’ death. But such a reading feels too easy, too external. It asks us to scapegoat rather than reflect.

The scapegoat mechanism is, of course, ancient. In Leviticus 16, the sins of the people are laid upon a goat, which is then driven into the wilderness—a ritual cleansing through projected blame. Judas becomes, for many, the Christian scapegoat. Yet Jesus’ whole mission was to dismantle the systems of blame and shame. What happens if we dare to sit contemplatively with Judas, rather than push him away?

Maybe we’re not so different from him.

Some scholars suggest that Judas may have been a zealot—someone longing for a Messiah who would overthrow Rome, who would fight fire with fire. If so, his betrayal was not born of simple greed or malice, but of bitter disappointment. Jesus wasn’t the Messiah he had hoped for. Jesus didn’t meet his expectations. And when our expectations of others collapse, if we’re not rooted in love and presence, we often lash out. We project. We seek to control. We harm.

Contemplatively, this raises a deep question: What happens in us when others don’t become who we want them to be?

Unexamined expectations can fester into resentment. Resentment, unspoken, can slip into hatred. And hatred, even when masked as piety or principle, can kill. This is not just Judas’ journey—it is the universal human journey. Without awareness, without contemplative space to hold our unmet expectations, we too may find ourselves betraying love.

But the Gospel invites us to notice more. Because Judas is not the only one who betrays Jesus.

Peter, too, denies Jesus—three times, no less. Both men fail Jesus in the hour of his greatest need. Yet tradition sees Peter as the repentant saint and Judas as the lost soul. Why?

The difference is not in the mistake, but in what they do with the shame.

Peter weeps bitterly. He lets his heart break. He remains available to Jesus, even through his brokenness. Judas, however, seems locked in his shame. He returns the silver but cannot return to love. His despair consumes him. It’s as if his ego, so bound to his failure, cannot imagine a world in which he is forgiven—let alone one where he forgives himself.

Here lies a contemplative insight: what do we do with our shame?

Shame can crush us, isolate us, silence us. Or, if held gently—compassionately—it can become the threshold of transformation. In contemplative practice, we are invited to face ourselves, including our failures, not with judgment but with loving awareness. We learn to sit with the parts of ourselves we wish to exile. We practice not pushing them away but listening, welcoming, integrating.

Jesus did not reject Judas. Even at the table, he feeds him. Even in betrayal, he calls him friend. But Judas could not receive that love. His self-hatred became louder than the voice of grace.

This is the tragedy—not that Judas betrayed Jesus, but that he could not believe he was still loved.

And here is the hope: that we don’t have to repeat that story.

In our lives, when we see the Judas tendencies in ourselves—the manipulations, the controlling, the acting out of disappointment—we are not condemned. The contemplative path offers us a way back: through truth-telling, through silence, through prayerful self-compassion. We are not our worst moments. We are not defined by failure. The invitation is always to return.

Holy Wednesday reminds us of this. In the darkness, Jesus still loves. Even the betrayer is included at the table.

Can we be brave enough to sit at that table too?

A Contemplative Practice: Sitting with Judas and Peter

This is a simple prayerful reflection to enter into in silence. Allow 10–15 minutes.

Find stillness. Sit comfortably, close your eyes if helpful, and take a few deep breaths. Let your body settle.

Bring to mind the story. Picture Jesus at the table, washing feet, breaking bread. Imagine Judas and Peter there—both beloved, both fragile.

Ask gently:

When have I acted like Judas—out of disappointment, unmet expectations, or control?

When have I acted like Peter—ashamed, but still open to grace?

Let these moments come without judgment. Don’t push them away. Just notice.

Now hear Jesus’ words: “Friend, do what you are here to do.” Let Jesus speak to you with the same tenderness he showed Judas and Peter.

Rest. Simply be in the presence of Christ. Let love hold the complexity of your story.

Close with this prayer (or your own):

God of mercy, help me face myself with honesty and gentleness. When I turn from love, guide me back. When shame grips me, set me free. Teach me, like Peter, to turn again—through tears, toward grace. Amen.

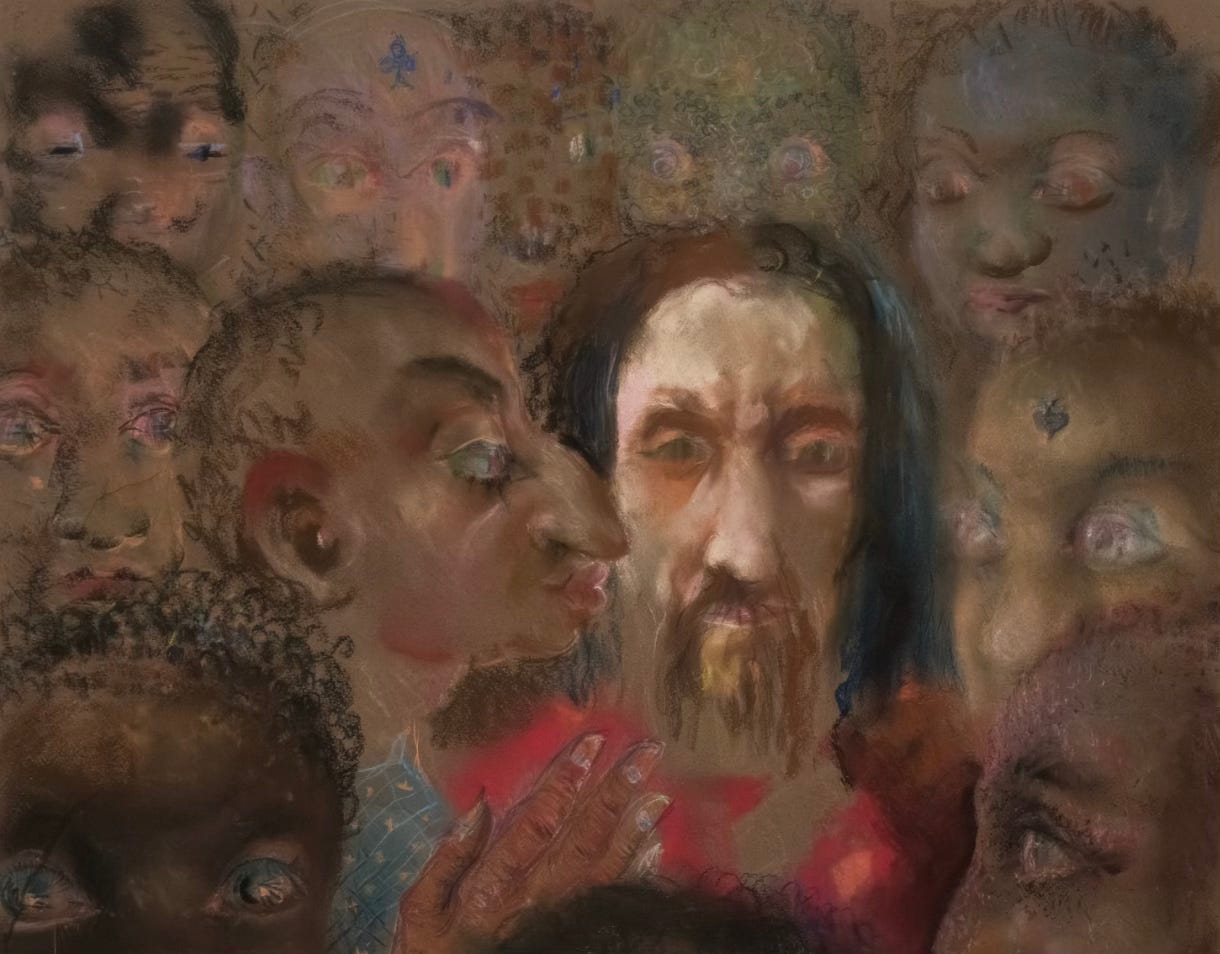

Art Work Title: Juuda suudlus Creator: Pehap, Erich (autor) Date: 1934 Providing institution: Tartu Art Museum Aggregator: Estonian e-Repository and Conservation of Collections Providing Country: Estonia CC0 Juuda suudlus by Pehap, Erich (autor) - 1934 - Tartu Art Museum, Estonia - CC0.

What happens when people don't become who we want them to be? That question you asked is haunting. I have certainly felt like a Judas in my life when I have not spoken up when things were wrong; when I took the easy road and denied someone the loyalty they deserved. Our God is forgiving, but I need to not make the same mistakes when I have received forgiveness.